This film has recently been restored.

This restoration was made from a 2K scan of the original 16mm reversal positive work print and the 16mm magnetic sound preserved at the French Film Archives.

Image scan: Adrien Von Nagel – Polygone étoilé/Film Flamme

Sound scan: Jean-Philippe Bessas

Image restoration: Mounir Al Mahmoud – ThePostOffice

Sound restoration: Monzer El Hachem

Color grading: Chrystel Elias – Lucid Post

Coordination, production: Mathilde Rouxel, Jinane Mrad – Association Jocelyne Saab

Available versions: French version – subtitles: French, English, Arabic, Spanish.

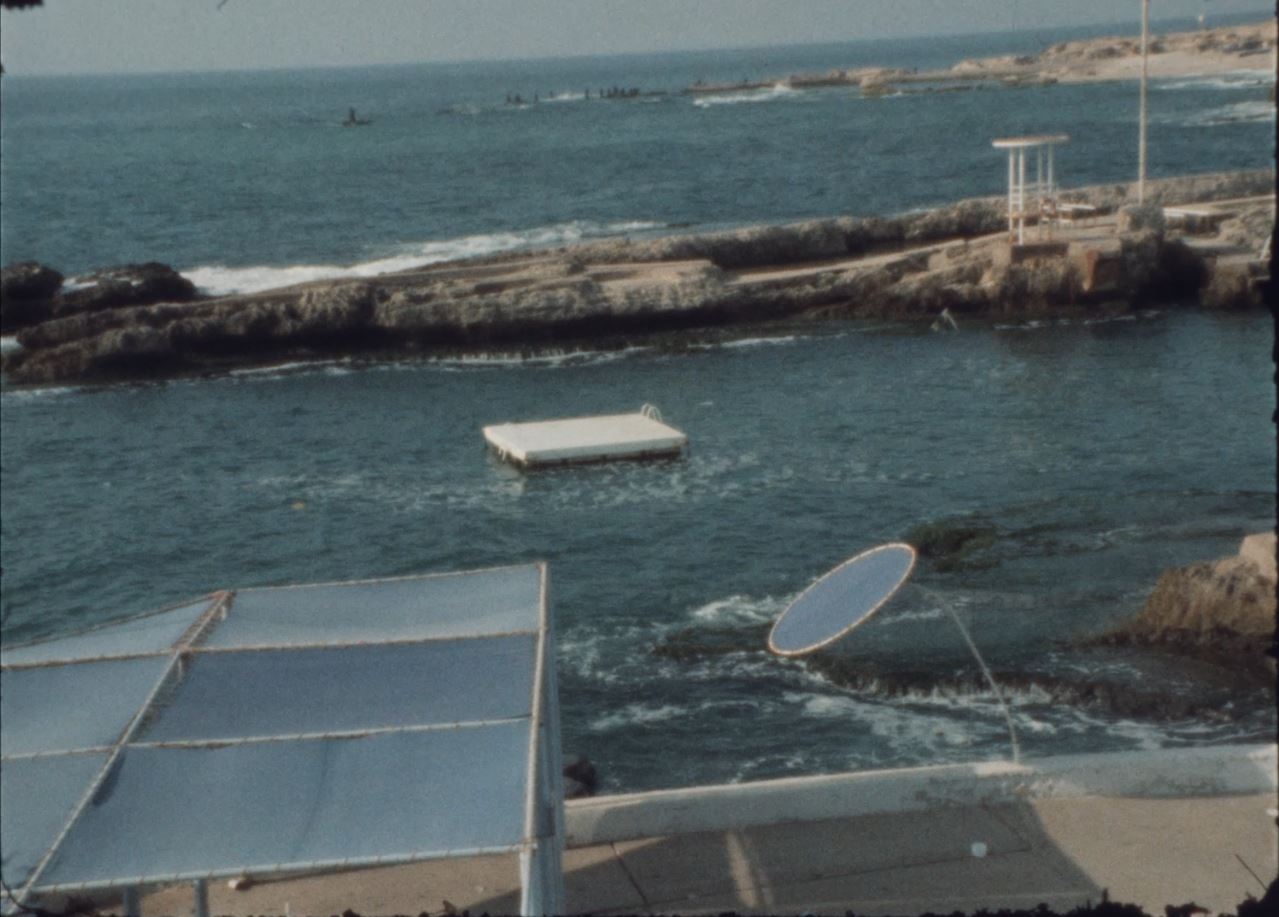

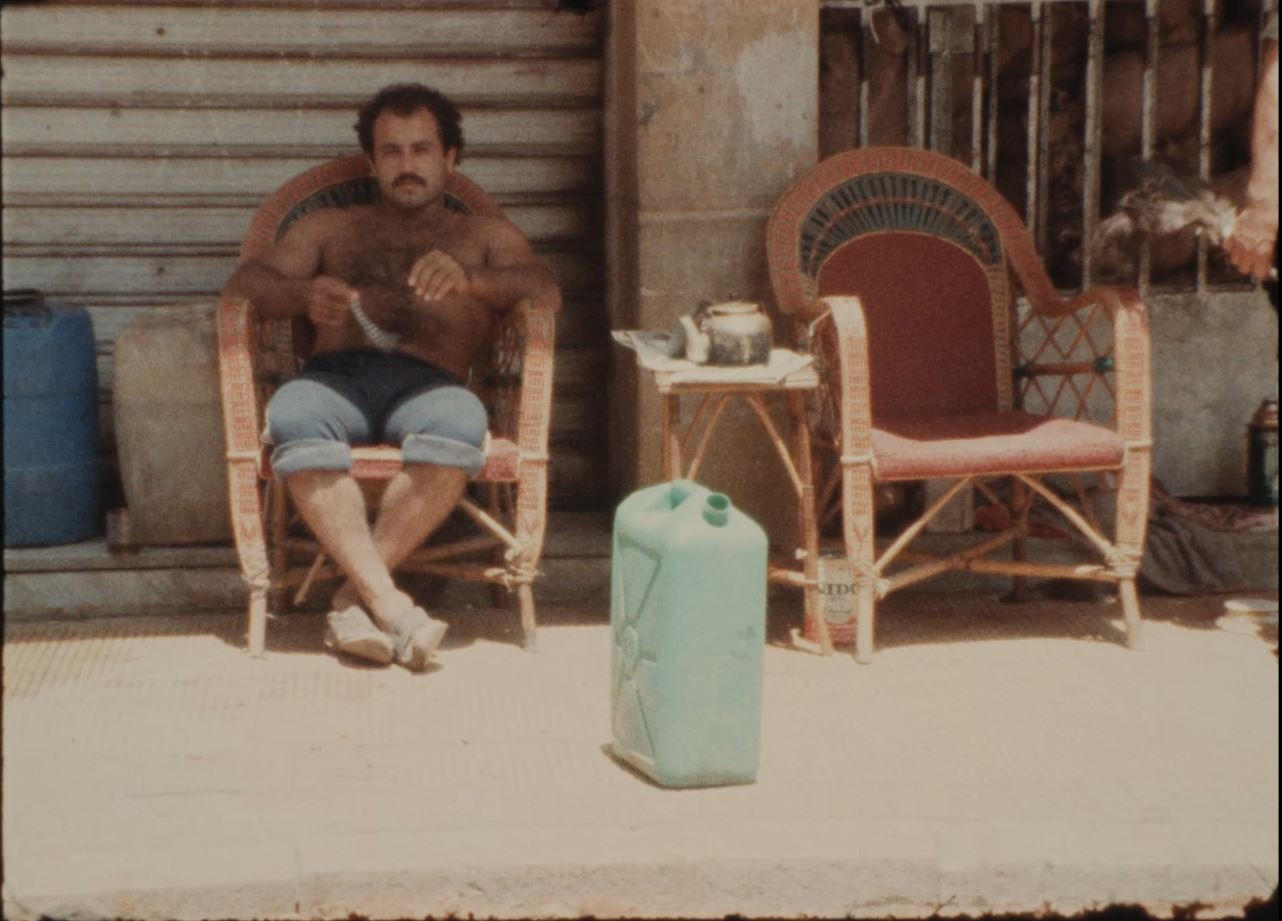

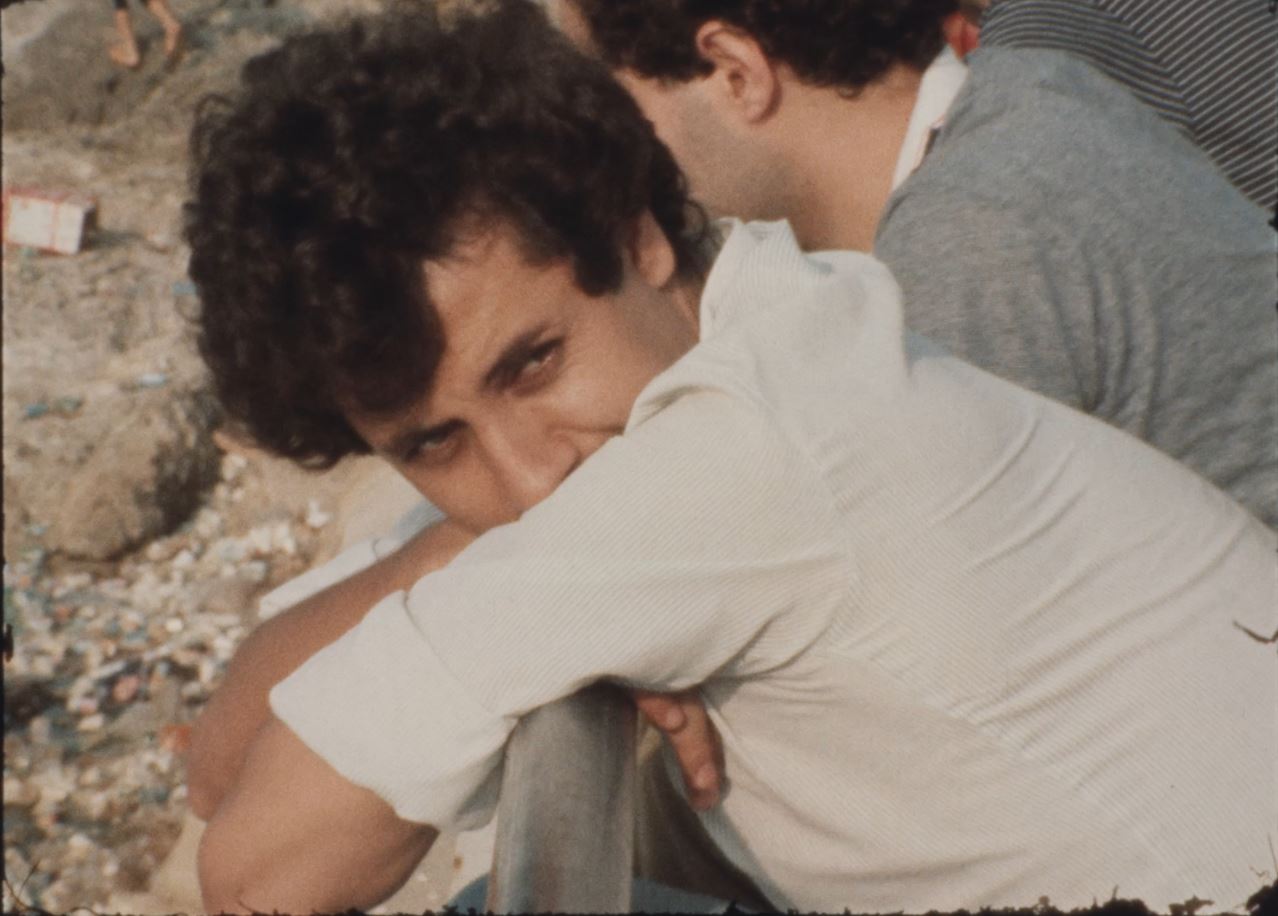

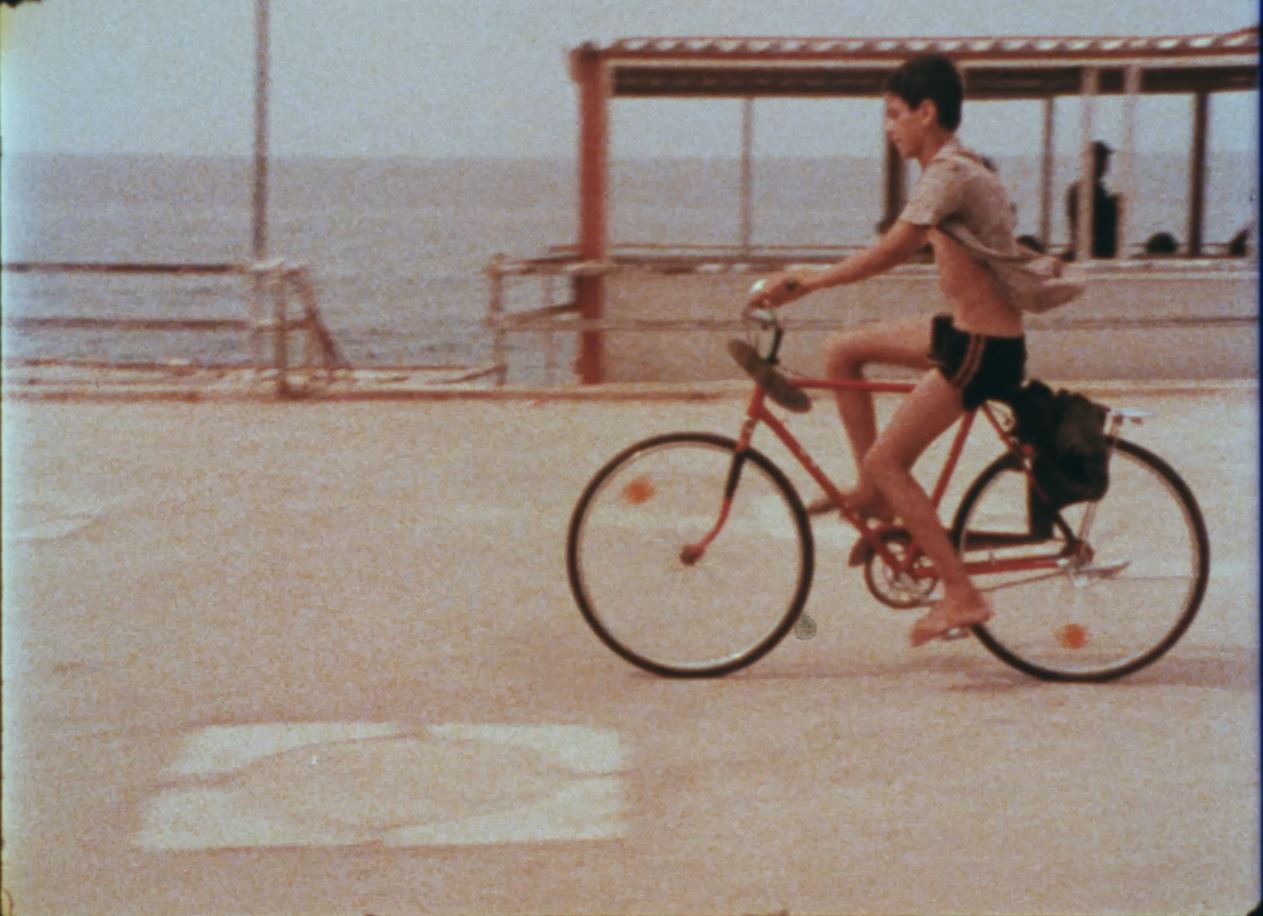

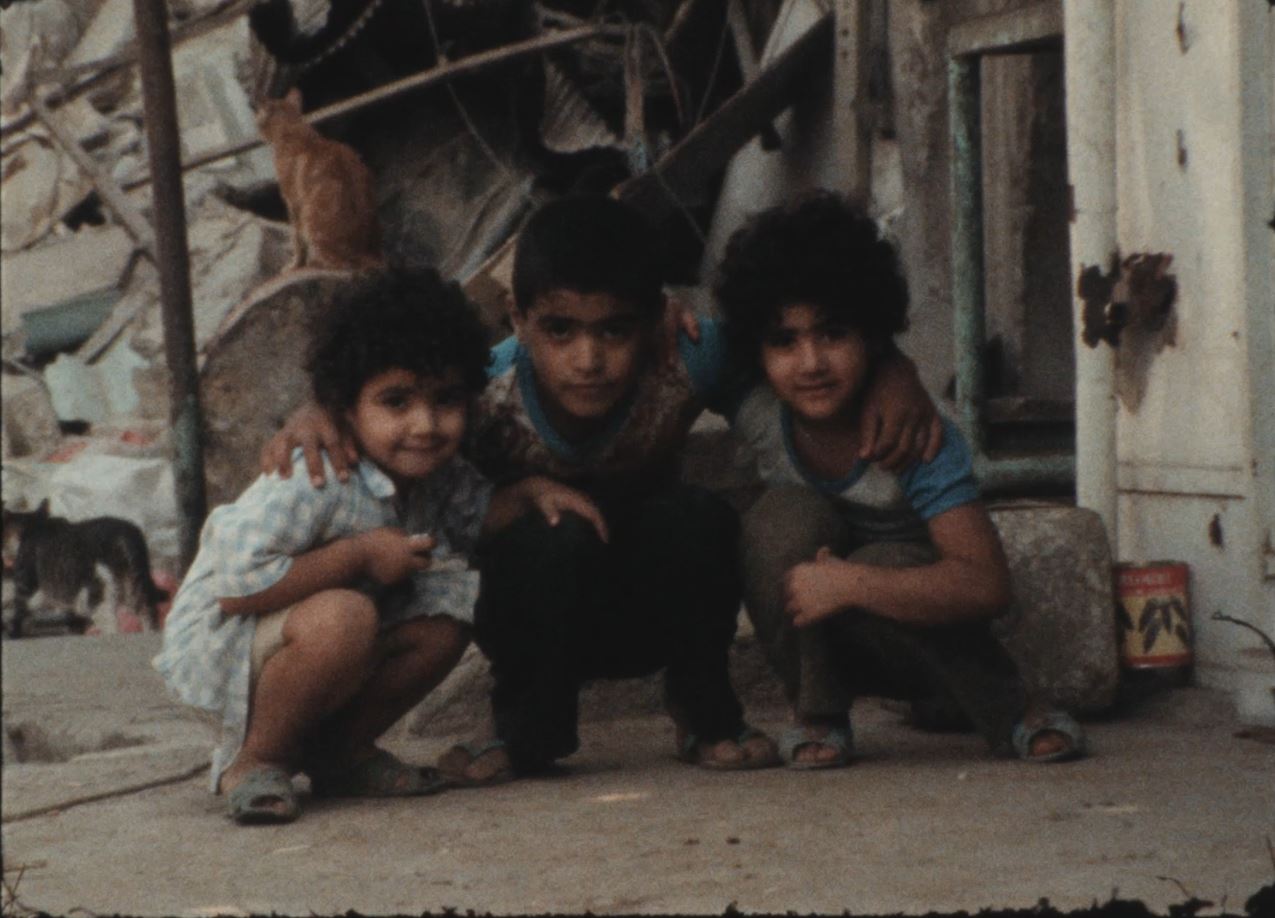

In July 1982 the Israeli army laid siege to Beirut. Four years earlier Jocelyne Saab saw her 150-year-old childhood home go up in flames. She asked herself: when did all this begin? Every place becomes a historical site and every name a memory.

There, that’s my house. At least, what’s left of it… And I can’t talk any more than others, it’s cynical, but… There’s my bedroom, we prepared a film in there.

The house had two storeys. Deep down, it’s not so bad, because after all they’re only walls, and we all got out alive. I’m thinking about the number of deaths that there have been over the last few days, on the one hand because of Israeli bombardments, on the other, internal fights. I don’t know, you have to ask yourself questions. The essential thing is to survive, to live.

It’s true that this house, it’s tradition, and that does something to one’s heart, because it’s 150 years of history. It’s my identity, too. The identity of all the Lebanese who are losing their home, their possessions. And since we don’t know to whom we should address ourselves, we no longer know who we are. Jocelyne Saab, opening interview of Beirut, My City

Jocelyne Saab’s word…