1948

Youth

Roger W., Beirut from the Air, 27 mai 1967 Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Jocelyne Saab was a filmmaker and photographer. She was born in 1948 and grew

up in Beirut. In 1973, she became a war reporter in the Middle East, covering the

October War for Magazine 52, the magazine of the third television channel in France.

In 1975, she directed her first feature-length documentary, Lebanon in Turmoil, which

was released in cinemas in Paris and distributed by Pascale Dauman. She then went

on to cover the Lebanese Civil War for fifteen years, during which time she directed

almost thirty films, including Beirut, Never Again, broadcast on France 2 in

1976, Letter from Beirut and Beirut, My City, broadcast on France 3 between 1978

and 1982. In 1977 both Egypt, The City of the Dead and The Sahara is Not for

Sale were shot and released in cinemas in Paris. In 1981, during the days following

the Iranian revolution, she shot Iran, Utopia on the Move , which received several

international prizes. In 1998, she went to Vietnam and directed The Lady of Saigon,

which was awarded the title of Best French Documentary by the French senate. It

was broadcast on France 2 and in many international festivals.

During a period of less than thirty years, Jocelyne Saab directed thirty

documentaries that were awarded prizes in European and international festivals.

However, her filmography is not limited to documentaries: in 1981, Jocelyne Saab

had her first opportunity to turn to fiction as Volker Schlöndorff’s assistant director for

his film Circle of Deceit, shot in Beirut during the war. In 1985, she went on to direct

her own first feature film, A Suspended Life, selected during the Directors’ Fortnight

at Cannes the same year and released in three cinemas in Paris. In 1993, she

dedicated a docufiction to the centennial anniversary of cinema, Once Upon a Time,

Beirut: Story of a Star, which is made up mostly of archival images and rushes from

old films set in Beirut before the Civil War. The film was broadcast on ARTE.

In 2005, her film Dunia, shot in Egypt and produced by Catherine Dussart, which

deals with pleasure as a central theme, provoked a scandal which resulted in Saab

being sentenced to death by Egyptian fundamentalists. Nevertheless, the film was

praised in many international festivals, and was amongst the feature films competing

at the Sundance Festival in the US. Five years later, Dunia had become a cult film in

the Arab world. In 2007, Jocelyne Saab turned to contemporary art, and put together

her first video installation on twenty-two screens at the National Museum of

Singapore. A retrospective look at the entirety of her works on the war, it is

entitled Strange Games and Bridges. Shortly after, she exhibited her first

photographs at the Abu Dhabi fair in 2007, followed by exhibitions at the Art-Paris

fair and in galleries in Abu Dhabi and Beirut in 2008.

In 2009, she finished a new feature film, What’s Going On?, shot in her city of birth.

In it, she questioned the possibility of Beirut's rebirth, and more generally the process

of creation in all its depth. In 2013, she taught at IESAV, the Institute of Performance

and Audiovisual Studies in Beirut, where she directed a feature film with students

about the charismatic figure of Henri Barakat. In 2013, she directed six films on the

theme of sex and gender in six cities in the Levant, reunited under the title Café du

Genre for the exhibition Au Bazar du Genre at the MuCEM in Marseille.

Throughout her life, she organized a number of significant events. In 1992, she

engaged in the rebuilding of the Lebanese Film Archive. To this end, she catalogued

over 250 films that mention Beirut and Lebanon before, during and after the War.

She was awarded the title of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters for this

monumental work, which she achieved while simultaneously editing her own

film, Once Upon a Time, Beirut. The film used footage from the archives and stands

as a testament to the depth of her involvement in the project. Using the same

archives, she also organized the cycle of projections “Beirut, One Thousand and

One Images” at the Arab World Institute in 1993, an event that presented all the Arab

films selected to be included in the Lebanese Film Archive. In 2013, she founded the

International Festival of Cultural Resistance, of which she was also president and

artistic director. She used the festival to screen Asian and Mediterranean films that

through their plot pose questions about the situation in contemporary Beirut and its

history. A cinema that heals the country’s wounds and makes us think about the

possibility of peace and respect between communities. This festival spread across

the entire Lebanese territory.

Towards the end of her life, she directed a last series of photographs, One Dollar a

Day, and several artistic videos: One Dollar a Day and Imaginary Postcard in 2016,

and My Name is Mei Shigenobu, which was released posthumously in 2019. During

her last years, she was working on a documentary about the hidden life of Mei

Shigenobu, Shigenobu, Mother and Daughter.

1970s

The October War (or War in the East) (1973, 8 min)

Documentary, 1973, color, France, 16 mm, 8 min.

1973

In 1973, she became a war reporter in the Middle East, covering the October War for Magazine 52 on France’s third TV channel.

Lebanon in Turmoil (1975, 75 min.)

Feature-length documentary, 1975, color, Lebanon, 16 mm, 75 min.

On several fronts: Lebanon, Egypt & Sahara

In 1975, she directed her first feature-length documentary, Lebanon in Turmoil, which was released in Paris. Lebanon in Turmoil distributed by Pascale Dauman.

She then went to cover the Lebanese War for fifteen years, during which she made almost thirty films, including Beirut Never again, broadcast on France 2 in 1976, or Letter from Beirutand Beirut, My City, broadcast on France 3 in 1978 and 1982. In 1977 both Egypt, The City of the Deadand The Sahara is Not for Sale shot and realeased in cenmas in Paris.

1980-

1990

Asia

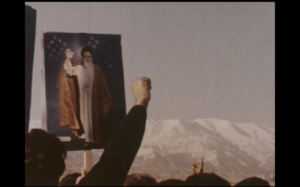

Iran, Utopia on the Move (1980, 52 min)

Documentary, 1980, color, Lebanon, 16 mm, 52 min.

In 1981, during the days following the Iranian revolution, she shot Iran, Utopia on the Move, which received several international prizes.

In 1998, she went to Vietnam and directed The Lady of Saigon, which was awarded the title of Best French Documentary by the French Senate. It was broadcast on France 2, and in many international festivals.

During a periode less than thirty years, Jocelyne Saab has made a total of thirty documentaries, which have won numerous awards at European and international festivals.

The Lady of Saigon (1998, 60 min.)

Documentary, 1998, color, France, beta, 60 min.

From documentary to fiction

However, her filmography is not limited to documentaries: in 1981, Jocelyne Saab had her first ipportunity to turn to fiction as Volker Schlöndorff’s assistand directer for his film Circle of Deceit , shot in Beirut during the war. In 1985, she went on to direct her own first feature film, A Suspended Life , selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes that same year and released in three cinemas in Paris. In 1993, she dedicated a docufiction to the centennial anniversary of cinema, Once Upon a Time, Beirut: Story of a Star, which is made up mostly of archival iamges and rushes from old films set in Beirut before the Civil War. The film was broadcast on ARTE.

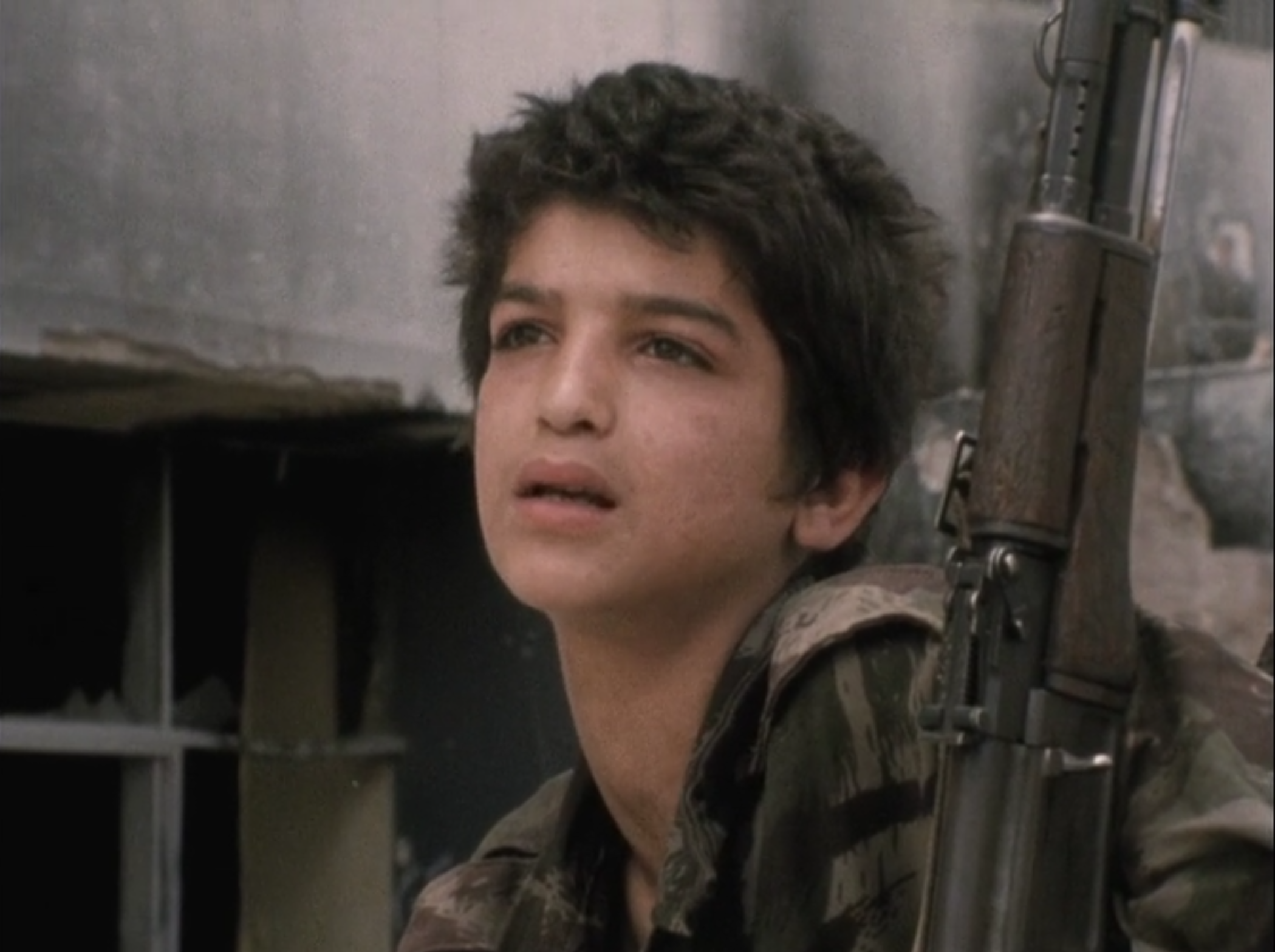

A Suspended Life (1985, 90 min)

Fiction, 1985, color, Lebanon / France, 35 mm, 90 min.

Once Upon a Time, Beirut: Story of a Star (1994, 100 min)

Docu-fiction, 1994, color, Lebanon / France, 35 mm, 100 min.

Artistic & cultural events

In 1992, she engaged in the rebuilding of the Lebanese Film Archive. To this end, she catalogued over 250 films that mention Beirut and Lebanon before, durung and after the War. She was awarded the Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters (Ordre des Chevaliers des Arts et des Lettres) for this monumental work, which she achieved while simultaneously editing her own film, Once Upon a Time in Beirut . The film used footage from the archives and stands as a testament to the depth of her involvment in the project. Using the samed archives, she also organized the cycle of projections “Beirut, One Thousand and One Images” at the Arab World Insitute (Institut du Monde Arabe), an event that presented all the Arab films selected to be included in the Lebanese Film Archive.

2000s

2005

In 2005, her film Dunia, shot in Egypt and produced by Catherine Dussart, which deals with pleasure as a central theme, provoked a scandal which resulted in Saab being sentenced to death by Egyptian fundamentalists. Nevertheless, the film was praised in man international festivals, and was amongst the feature films competinf at the Sundance Festival in the US. Five years later, Dunia had become a cult fim in the Arab world.

2007-2008

In 2007, Jocelyne Saab turned to contemporary art, and put together her first video installation on twenty-two screens at the National Museum of Singapore. A retrospective look at the entirety of her works on the war, it is entitled Strange Games and Bridges.

Shortly after, she exhibited her first photographs at the Abu Dhabi fair in 2007, followed by exhibitions at the Art-Paris fair and in galleries in Abu Dhabi and Beirut in 2008.

2009

In 2009, she finished a new feature film, What’s Going On? shot in her city of birth. Shortly after, she exhibited her first photographs at the Abu Dhabi fair in 2007, followed by exhibitions at the Art-Paris fair and in galleries in Abu Dhabi and Beirut in 2008. In 2013, she taught at IESAV, the Institute of Performance and Audiovisual Studies in Beirut, where she directed a feature film with students about the charismatic figure of Henri Barakat. In 2013, she directed six films on the theme of sex and gender in six cities in the Levant, reunited under the title “Café du Genre” for the exhibition “Au Bazar du Genre” at the MuCEM in Marseille.

What's Going On ? (2009, 80 min)

Fiction, 2009, color, Lebanon, mono-HDTV, 80 min

2010s

2013

In 2013, she founded the International Film Festival of Cultural Resistance, of which she was also president and artistic director. She used the festival to screen Asian and Mediteranean films that through their plot pose questions about the sitaution in contemporar Beirut and its history. A cinema that heals the country’s wounds and makes us think about the possibilit of peace and respect between communities. This festival spread accross the entire Lebanese territory.

International Film Festival of Cultural Resistance

Insatiable projects

At the end of her life, she directed a last series of photographs, One Dollar a Day, and several artistic videos: One Dollar a Day and Imaginary Postcard in 2016, and My Name is Mei Shigenobu, which was released posthumously in 2019. In her later years, she was working on a documentary about Mei Shigenobu’s hidden life, Shigenobu, Mother and Daughter.

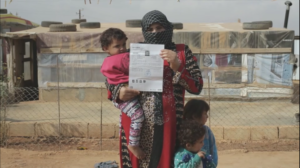

One Dollar a Day (2016, 6 min)

Art video, 2016, Lebanon, digital, 6 min.

Imaginary Postcards (2016, 6 min)

Art video, 2016, Turkey, digital, 6 min.

My Name is Mei Shigenobu (2018, 6 min)

Art video, 2018, Lebanon, digital, 6 min.

“Because of her films, and because of her whole life so far, I see in Jocelyne Saab one of the bravest, most intelligent and above all freest people I know. His freedom of thought and action cost him dearly. At times, it was a matter of life and death. Few people, men or women, have suffered as much to remain worthy of themselves, to survive in a way that makes sense, in a world as hostile or indifferent as ours.

Jocelyne deserves recognition for her work, and few people deserve our admiration as much as she does. I’m happy to be able to say that.”

Etel Adnan