This film has recently been restored.

This restoration was carried out using a 2K scan of the original 16 mm reversal positive work print and the 16 mm magnetic sound preserved at the French Film Archives.

Image scan: Adrien Von Nagel – Polygone étoilé/Film Flamme

Sound scan: Jean-Philippe Bessas

Image restoration: Adrien Von Nagel – Polygone étoilé/Film Flamme

Sound restoration: Monzer El Hachem

Color grading: Chrystel Elias – Lucid Post

Coordination, production: Mathilde Rouxel, Jinane Mrad – Association Jocelyne Saab

Available versions: French version – subtitles: French, English, Arabic, Spanish; Arabic version

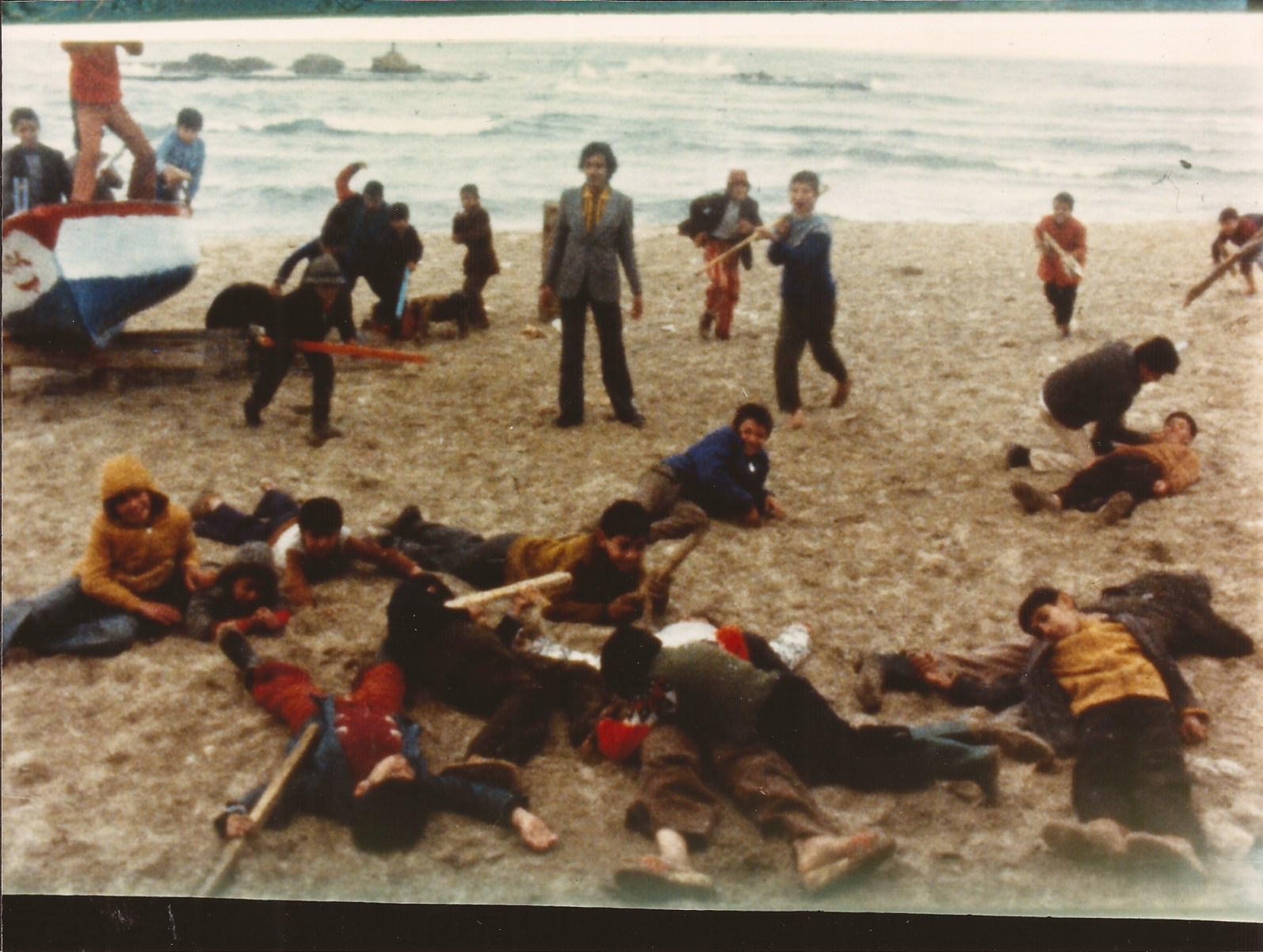

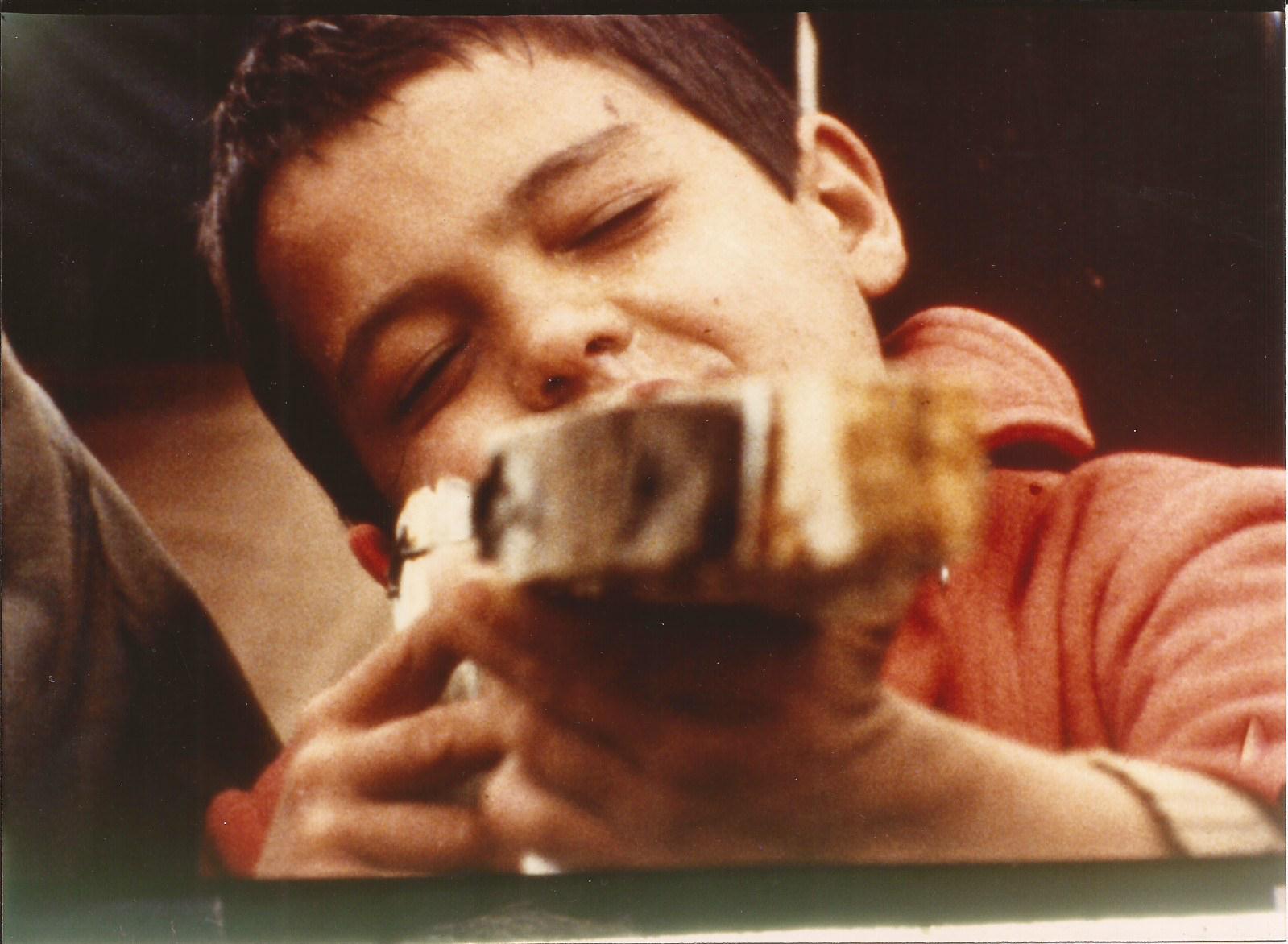

Days after the massacre in Karantina, a predominantly Muslim shanty town in Beirut, Jocelyne Saab finds and meets children who have escaped, and who are deeply traumatized by the horrific fighting they have seen with their own eyes. Jocelyne gives the children crayons and encourages them to draw while her camera rolls. She makes a bitter discovery: the only games the children engage in are war games.

The war would quickly become a way of life for them as well.

Jocelyne Saab’s word…

After Lebanon in Torment, I had at my disposal a camera and a car, and I had my house. It’s true that I had money problems, I didn’t have much. And so, I take the chief operator and I say to him, “come on, let’s go!”, because I had spent the night talking with journalists who were coming back from Karantina (the refugee camp that had just been taken by the Phalanges), and I had seen the end of the massacre. What’s more, I had also learnt that a friend of mine, no doubt influenced by her entourage, had found it amusing to film it from the side of the killers. Later, she suffered greatly, for other reasons.

When the bidonville had been stormed, many adults had been slaughtered in cold blood, and once the refugee camp had been conquered, the assailants popped champagne, right next to the corpses. Children survived. When they came out at night, I had nothing, not even a lamp, but I followed their path to find out where they were going because they could no longer get to the bidonville in Karantina which had just been razed to the ground and their parents had been killed. I saw that they were going into the city’s chic beach huts – Saint Simon, Saint Michel – that then became bidonvilles, which still exist today.

So, I buy paper, colouring pencils, and I go to meet them, starting the next day. That gives me just enough time to call my chief operator from the TV, Hassan, who works with me, and I say to them: I am coming to film you on Sunday, you will show me your games. And they play war, on the beach, but it very quickly becomes very violent, so much so that I am forced to tell them to stop playing and that I have to take two of them to the hospital to be stitched up, because they had wounded each other. Then, we go back. And that’s when I live the most powerful moment. They were a bit sheepish, because three of them had been injured, but it was as if they were letting out the surrounding violence that they had lived through and accumulated within themselves – don’t forget that they had just come out of a massacre. I find them between the chalets set up like a chic little village and I propose that we continue filming. And there, the children who had been injured and traumatised by what had just happened free themselves and mime the massacre. And I film it.

I guard my materials ferociously, I take the first plane for Paris and go straight for the television. At the time, that’s how we did it: either we slipped into Television via our friends, or we followed the traditional procedure, which is what I did on that occasion. This time I knew that I had something hefty to offer. I am going to see my chief editor (Jean-Marie Cavada) and I say to him: “develop this roll of 16mm, look at the images, and if you like them, I’ll edit the film”. They develop them, don’t get them back to me, give me an editor who works in a TV style. And little by little, journalists come by the editing room and ask if I had staged what the children were doing. How could I have done that?

Words collected by Olivier Hadouchi in Paris in 2012.